- Home

- Karen Branan

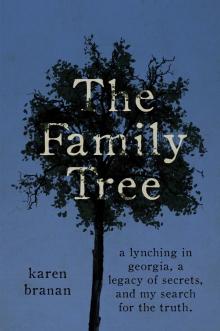

The Family Tree Page 2

The Family Tree Read online

Page 2

Through the 1940s and into the 1950s we made that drive, the four little cousins punching and poking one other as we drank in the sights from my aunt’s crowded, wool-upholstered backseat. Acres of cotton fields, plowed and planted in fiery heat by Negro men behind plodding mules. Chained black convicts, pickaxes pounding rock along the narrow highway, chanting their mournful dirge. Miles of clay-coated green kudzu, dangling from power lines. A “Visit the Everglades” billboard with a picture of a glass-bottom boat posted on land owned by Big Mamma, my paternal grandmother. Mangled carcasses of roadkill all along the highway—possums, coons, dogs, and rattlesnakes grazed on by buzzards.

Halfway to Hamilton, in the middle of nowhere, our tires rattled across the wooden bridge over Mulberry Creek, just past the Big House—a large white two-story farmhouse with a deep wraparound veranda, where my father grew up. We’d turn left at Mamie’s cabin, back in the woods on Williams land. There she’d be waiting, my grandmother Williams’s old cook, likely the granddaughter of a Williams slave, now skin and bones. With a wide, toothless grin, she’d reach out to touch us “babies” as she deposited her weekly sweet-smelling bundle of fresh laundry, tied up in a white sheet, onto the floor of the backseat. Tucked into its center was a jug of muscadine wine, which, as we cousins grew older, we found courage to sip secretly.

As Nana’s poky car finally nosed into town, having stopped at least once for someone, usually my cousin Steve, to get a roadside whipping, we’d first pass the massive Beall-Williams-Mobley house, handed down in my father’s family since the 1830s and still occupied by cousins. Then, to our left, on the square, we’d see the once-gleaming, twenty-one-foot marble Confederate soldier, now blackened by time and neglect, but still honored each Confederate Memorial Day when lines of elders and schoolchildren laid wild wisteria at his feet. “Fate denied them victory but crowned them with glorious immortality” read the words inscribed on its base.

Downtown Hamilton consisted of little more than four square blocks around Monument Square. Three elegant houses anchored and decorated three of its compass points, all of them large, boxy antebellums with stately columns, balconies, and spacious verandas that announced, “The best people live here.” Two had belonged almost from the beginning to members of my father’s extended family, to Williamses, Bealls, and Mobleys. Strewn among these landmarks were gabled Victorian farmhouses with gingerbread trim, white picket fences, and neat flower beds, as well as simple cottages, old stores, and warehouses smelling of seed corn and animal feed, smoked hams, and sturdy bolts of calico. A scattering of outbuildings peeked from behind and between the larger edifices—chicken coops and smokehouses, a tannery, a coffin maker’s premises.

Among the public shops were a Williams uncle’s drugstore, the post office, two gas stations, and Evelyn’s Café. Evelyn was my mother’s younger sister, a sexy, blue-eyed, tough-talking, chain-smoking woman. Around nine hundred people populated Hamilton proper in those days, six hundred of them black and three hundred white.

After bumping across the railroad track at the depot, we’d pass a bevy of Negro shacks raucous with orange hollyhocks in summer, and then we’d pull into our Hadley grandparents’ gravel driveway. It was a plain, small house, six rooms—two front, two middle, two back—with screened porches back and front. Beside it blossomed G’mamma’s riotous garden of snapdragons, sweet peas, roses, zinnias, and marigolds. Inside, her house was adorned with her creations: hooked rugs, French-embroidered baby dresses, knitted afghans, patchwork quilts, crocheted antimacassars, and needlepoint chair seats.

Though we’d eaten less than an hour earlier, the kids would make a beeline for G’mamma’s red-and-white kitchen, where leftover fried chicken and biscuits, still warm in the oven, prepared by Hopie, her maid, awaited us. After that there were endless possibilities for pleasure. We could ride the cow in the back pasture or pretend the propane tank or cotton bales were horses. Or we could play fort in the smokehouse or Tarzan in the apple tree. Or we could swipe strawberries from our great-grandmother Deedie’s garden (the “quarters,” as it was once called), cut paper dolls from old Sears catalogs, read the Saturday Evening Post, shoot our cousin Buster’s Red Ryder BB gun at birds and one another, duel with spears torn off G’mamma’s massive Spanish dagger bush, or line the steel rails across the street with pennies so the afternoon Man O’ War would flatten them as it chugged by.

But our favorite Sunday pastime was a visit to the courthouse with Dad Doug. By that time, Marion Douglas Hadley, my maternal grandfather, had been sheriff for more years than anyone cared to count. I was proud to be the granddaughter of a sheriff. Dad Doug was tall and lean, a Gary Cooper kind of guy with clear blue eyes, wavy brown hair, and a face deeply furrowed by the sun. He kept his badge in his wallet and his gun in his glove compartment, drove a regular unmarked Ford like everyone else, and wore the khaki shirt and pants and white socks of every other white farmer in Harris County, along with a straw hat in summer or a felt hat in winter. His only effort at a uniform was a thin black tie.

Every summer, my sister and I would spend a week or two in Hamilton. We ate breakfast at sunrise, awakened by G’mamma’s call and the irresistible smell of bacon, eggs, toast, and coffee. Sometimes when we lay abed too long, Dad Doug would swoop one of us up by the feet and hold us upside down until we squealed. This playful side, however, was a rarity. Most often we’d be at the table in our pajamas, waiting, when Dad Doug would walk in, tousle our hair as he sat down, and say, “Hey, here, girls.” Those are among the few words I can remember coming from his mouth, other than “Don’t touch that gun,” a remark he made specifically to our cousin Steve one day when he left us briefly in the car at his farm. Steve disobeyed him, and the gun lay in several pieces when he returned. We sat quietly as the two took a little walk into the woods. Nothing was ever said about it.

On our Sunday outings, he’d take us by Shorty Grant’s Amoco station for moon pies, orange Nehis, or chocolate ice cream in paper cups with tiny wooden spoons. The station reeked of rubber and oil and gas fumes. Shorty was a little bowlegged man with a potbelly and a kindly way with kids. Snacks were always on the house for the sheriff’s grandchildren.

In warm weather, Hamilton police chief Willie Buchanan, baggy trouser legs rolled to his knees to reveal pasty calves, a Jesus fan in one hand and a Coca-Cola in the other, would be sitting on the park bench in front of the courthouse. While the two men chatted on the bench or Dad Doug worked in his office, we children had free run of the stately mahogany courtroom. There we performed elaborate trials. Because we’d never actually watched a trial, except in westerns, ours were concocted in our wild imaginations or, more often, inspired by the gossip we overheard among the grown-ups on G’mamma’s front porch. Since there were only four of us, sometimes five when Cousin Buster joined us, we took turns being judge, jury, sheriff, prosecutor, and criminal. Once or twice, when one of the two jail cells out back was empty, we’d extend our drama into that damp stone place with all its smells and whispers.

Summers in Hamilton were even better than our Sunday trips, for then my sister and I were allowed to splash in Mulberry Creek with the black Weaver children who lived on Dad Doug’s farm. Best of all, we got to wait tables at Evelyn’s. It was a simple place, long and narrow, with a linoleum floor, wide, flyspecked front window, and metal tables. Our aunt Evelyn was the star, flitting from kitchen to dining room, issuing orders to the cook, flirting, joking, scolding, and teasing her customers, most of whom were kinfolk either by blood or marriage. There were no menus, and the folks who came in for lunch simply ordered what they had a taste for—country-fried steak, ham, BLT, chicken salad. If the makings weren’t in the kitchen, my sister and I dashed out the back screen door and into the grocery store to get them. No one seemed to mind the wait, caught up as everyone was in the gossip of the day or just doing their “bidness.”

Despite a sluggish ceiling fan, the café was hot. Back in the kitchen, Hopie, the black woman who worked for Evelyn when she

wasn’t taking care of G’mamma or in jail for drunkenness, expertly shuffled half a dozen frying pans at once, sweat sliding like molasses down her ample shoulders. The dining room was filled with the hum of the men’s serious murmurs, occasionally cut by the sharp exclamations of women, edged with mock outrage and the tantalizing whiff of scandal and secret, or sudden laughter that cut through the café like a burst of bright light.

Some days we’d stay in the house, reading, playing paper dolls, G’mamma’s Singer ticking in the background as she made dresses our mother would force us to wear, that cigarette always dangling from her bright red lips, her canary chirping away in its cage. We perked up when the phone rang, signaling the soap opera about to begin. This was “Miss Berta” (as G’mamma was known to her many friends) at her best: the lifted eyebrow, the wry lip, the arch remark, the upward roll of the eyes, the flourish of a bejeweled hand.

Those woods, she once told me, referring to the unknown, are full of things you do not want to know about. But I did want to know. I squatted at keyholes or simply listened openly, my ear straining for some meaning in the rapid whispers and hushed drones of my grandmother and her daughters as they rocked on the porch or sat in the overheated parlor in winter, or when G’mamma took us to Little Sister Hudson’s elegant antebellum house or the smelly little “old folks’ home” where her aunt lived. Our fascination with the gossip at the latter was quickly exhausted by the suffocating heat of coal-burning fireplaces, even in summer, and the death grip of Aunt Betty’s bony hands on our arms as she tried to show us her love and keep us from leaving. The best secrets came from G’mamma and her friends Flora Hardy, Miz Sprayberry, and Alex Copeland, who used to be the preacher at Hamilton Baptist Church but was now the organist. “Run out of town.” “Born out of wedlock.” “Buncha men showed up at her screen door.” “Ran off with . . .” “Caught them down by. . .” The fine hairs on the back of my neck sprang up at these hints of scandal.

G’mamma was always busy with something, except when one of her migraines came on. When that happened she’d retire to her room, door closed, room darkened, a cool cloth over her forehead. Evelyn and Hopie would tiptoe around and call the doctors, a married couple, until one or the other showed up with a black bag and a hypodermic needle.

G’mamma’s mother, Deedie, lived in the back bedroom, next to the kitchen. She didn’t gallivant with us and she didn’t wait on G’mamma, her only child, when she was having her migraines. My great-grandfather Mr. Bob had been a terrible drunk, and I think she was just worn-out after all those years of riding herd on him. G’mamma called her father a “bridge builder.” Later I learned that chained convicts built those bridges across the Mulberry and the Ossahatchee creeks and that “Mr. Bob,” pistol and bullwhip at the ready, told them what to do and made damn sure they did it. Deedie’s room was always darker and cooler than the rest of the house and when she wasn’t out back in a calico sunbonnet, tending her strawberries, she was there, sunk deep inside herself, rocking and dipping snuff.

Deedie was plain as a paper sack, a simple country woman who knew more than she let on. I sensed that even as a child. She represented “history,” and that, in my mother’s family, felt a bit forbidden, a thing best locked in an old trunk; but it was a thing this curious child longed to unwrap, much like Deedie’s old trunk, stuffed with yet-unwrapped gifts from years gone by. “Got everything I need,” she told me when I asked why she hadn’t opened them.

As I grew older, G’mamma’s migraines got worse. She spent most of her days in bed, calling for Hopie, who’d left Evelyn’s Café to become her maid, to notify the doctors. Everyone crept around her. “Don’t tell Mamma,” her daughters whispered about almost everything. One Christmas, just as lunch began, one of my cousins accidentally set the field across the street ablaze with firecrackers. It was a dry winter, and flames raced quickly through the brown grass. Platters of turkey, dressing, and candied yams were being placed on the crocheted tablecloth, and the outwardly calm daughters rounded up the kids to eat, hissing, “Don’t tell G’mamma. Just eat like nothing’s wrong.” The smoke billowed so thickly we could smell it in the dining room, and while the men were out beating the fire with branches and blankets, the women and children said blessings, smiled, and ate as if nothing whatsoever was wrong. G’mamma didn’t seem to notice.

I thought maybe something bad had happened to G’mamma long before. Once, when I was around ten, she said something mean about “nigrahs,” and my mother shushed her, glancing my way and saying of me, “She likes them.”

“Won’t like ’em so much once one of ’em rapes her,” G’mamma shot back, those haughty, smack-certain eyes boring into mine.

“Has one ever raped you?” I asked, both amazed and curious. “Well, no.” She stammered a little, not expecting such a question from even this child. “But I was driving alone one night and, standing right out in the middle of the road, butt-nekked, was a nigrah man, right there in my headlights. Scared the living daylights out of me.” That didn’t sound to me even close to rape (which my mother had defined for me when I asked as “a man taking advantage of a woman,” and the boys next door had later filled in the blanks), but I kept my mouth shut.

I tiptoed back into Hamilton that summer of 1993, carrying articles about Norman Hadley’s murder and the lynching just to remind myself, if need be, that I hadn’t made the whole thing up. I didn’t expect much cooperation, or even living memory of the event, nor did I expect to find documents. I figured few had been created and that those that had, had long ago been destroyed by flood or fire, the way it happens with certain pieces of paper in small-town courthouses. Those disappearances had become so common in recent years that an archivist at the Georgia Archives recited for me a law I should quote if I suspected something amiss in Hamilton.

Louise Teel was eighty-four years old that fall of 1995 when I returned with questions about the lynching burning inside me. A large, jovial white-haired woman, she was my mother’s first cousin and the closest thing to a genealogist I’d known on the Hadley side of the family. I found all two hundred pounds of her planted in the recliner the army gave her cousin Helen when she retired as a nurse. Helen, once and always a missionary, had died sitting in that chair at Muscogee Manor less than a year earlier. Louise still cried when she talked about Helen, but Louise cried when she talked about most things, laughing and crying at once. Except for her mother, Sheriff Marion Madison, “Buddie” Hadley’s eldest daughter, she was the only Hadley I ever knew who had any passion. She just loved life, loved to talk. A simple country woman, she’d lived most of her life with a husband from one of the meanest, most powerful moonshine families in Harris County.

I asked Louise if she’d ever heard of Norman Hadley. “Oh, yes,” she said, as if I’d asked her what she had for lunch. “He was the one who was murdered.” Just like that. “By whom?” I asked. “Oh, a bunch of nigras shot him. Then they hung ’em. I saw it. I was only two then, and everybody told me I couldn’t remember anything, being so young, but I do. I remember that woman’s tongue. I’ll never forget that woman’s tongue and the bullet hole.”

“How’d it happen?” I asked.

“I wish I knew, Karen,” she said. “I wish I knew. I asked that question all my life and all I ever got was silence.” She stopped, shredded the tissue in her lap, and shook her head for a while. “Just silence. Or they’d say I had just made it all up. All I can say is they must have had something to hide.”

CHAPTER TWO

Plantation Politics

The initial aim of Georgia’s founder, James Edward Oglethorpe, and the colony’s twenty trustees was to create an Eden in which England’s “downtrodden” would find opportunity to become sturdy yeoman, growing grapes for wine and mulberry trees for silk. In 1732, sensing in advance these would bring Georgia to grief, Oglethorpe convinced Parliament to outlaw liquor, slaves, large plantations, lawyers, and Catholics.

His noble ideal quickly died. Oglethorpe screened applicants so c

arefully that few of the “unfortunates” made it through. Mulberry trees and grapevines proved resistant to conditions in the colony. From 1732 to 1750, the plantation forces pushed their case, and when trustees returned their charter to the Crown in 1750, and Georgia became a royal colony, the dream of a pure small-farm Eden evaporated. From the exhausted and shrinking lands of North Carolina and Virginia came planters and the families they’d enslaved. These included my Williams and Hadley ancestors, who sought the fertile black soil along the Chattahoochee River, and the pure, sweet whiskey-making waters of its tributaries. They waited impatiently in the northeastern counties, already cleared of troublesome “savages,” until most of the Muscogee and Cherokee bands along the Alabama border were driven out or murdered and they could claim their 404 1/2-acre plots, which they had already won in lotteries.

Georgia soon led the world in cotton production, thanks to the advent of the cotton gin and the depletion of soil to the north. A slave population of just under 30,000 in 1790 billowed to over 100,000 by 1810. On the eve of the Civil War, nearly half a million slaves accounted for 44 percent of the state’s population; 75 percent of those lived in the fertile Black Belt, where Harris County was located.

From its beginnings in 1827, Hamilton, Harris County’s seat, attracted residents devoted to law, religion, and education. Columbus, established one year later in 1828, just south of the county line, sat on the banks of the magnificent Chattahoochee, which flowed into the Gulf of Mexico. Developers envisioned a booming port city with Black Belt cotton plantations supplying a textile industry the equal of New England’s. My paternal great-great-grandfather, General Elias Beall, was one of five commissioners named by the governor to lay out the city.

The Family Tree

The Family Tree